As I grew up I always had the opportunity to access green space and parks. My mom’s side of the family are descendants of the “Wandervogel” movement, a social movement in Germany that aimed to bring individuals back to nature. My grandma, born in 1941, always told stories of my great grandfather on hiking expeditions with friends before the Nazi control of Germany and eventual conscription into the army. Most childhood days were highlighted by visits to a giant white oak with my grandma. In the morning I’d wake up wide-eyed and ask, “Are we going to the big tree today?” As I’ve grown older I’ve become an avid camper, hiker, and a passionate advocate for public lands. I’ve spent most of my life outside, but my access to green spaces increased tenfold this past summer due to my internship at the Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

The official position name was Community Engagement interpretation. My duties ranged from historical, natural, and cultural interpretation to hard labor like invasive plant removal and trail work. On certain days I would report to the Cuyahoga Valley and on other days I would visit schools in the Akron and Cleveland metropolitan areas to educate about the National Park Service. The most refreshing part of the internship was that I was exposed to a large palate of different opportunities for community enrichment. Programs and activities changed from day to day. Throughout the internship, I gained experience working with individuals of different ages, ethnicities, religious perspectives and neurodiversity. From each encounter, my belief in universal access to public parks strengthened. I’ve always considered myself a spokesperson for public lands but after this summer I firmly believe there must be a paradigm shift to have park access for everyone regardless of SES income and economic and social marginalization.

The goal of a Community Engagement Interpreter is to educate the public about the tangible and intangible meanings in a resource. Ideally, an effective Community Engagement interpreter can educate about empirical historical and natural facts and also persuade an audience to look deeper with dialogic questions. For example, a Community Engagement Interpreter at Yosemite could educate the public about how El Capitan was formed and how climber culture has grown in Yosemite but could also stir conversation with a question like “What is the value of preserving natural resources from our increased desire for adventure?” Community Engagement Interpreters also ensure the park system is readily accessible for a diverse pool of individuals.

Newton Jury, former director of the National Park Service, once put forth the idea that “The National Park System also provides history and prehistory, a physical as well as spiritual linking of Americans with the past of their country” With Jury’s sense of the National Park’s Service’s duty in mind, the primary project that I worked on at the Cuyahoga Valley National Park was a historical exhibit about the History of African Americans in the Cuyahoga Valley and Cleveland area. The project was inspired by a collective discussion between all the Park Rangers and Community Engagement interns regarding the under-representation of marginalized individuals in the Cuyahoga Valley’s interpretation department. One of the few physical representations and exhibits about African American history in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park is a handful of interactive exhibits in the Canal Exploration Center.

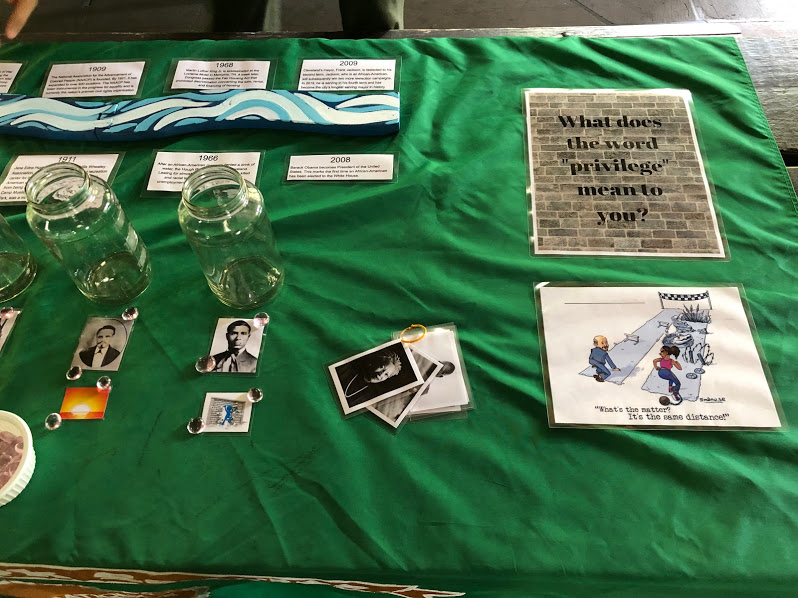

The essential theme question of the pop-up exhibit was “What do the stories we preserve say about us as a society?” The essential theme question was designed to explore the maxim “History is written by the victors” and the scarcity of marginalized narratives in public historical discourse at times. Other dialogic questions that our team chose to highlight were

“What is a story in your life you’d like to be remembered by?”

“Have you ever felt your achievements were being ignored or unnoticed?”

“What does the word privilege mean to you?”

Each question is written on a whiteboard and guests are encouraged to share personal stories and write on the whiteboard.

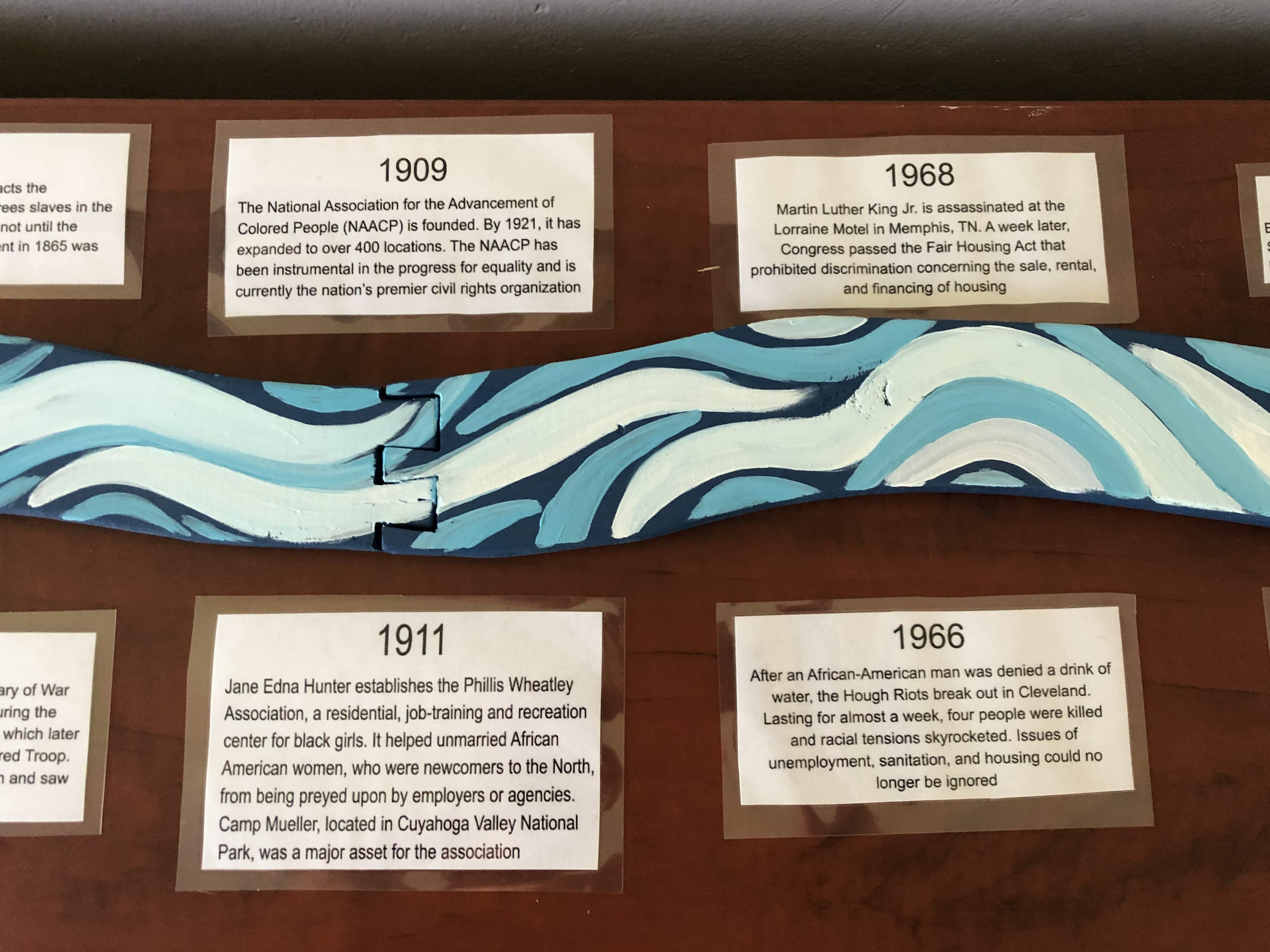

In addition to our essential theme question and dialogic questions, the bulk of our pop-up includes historical stories, descriptions of African American figures in Northeast Ohio history, oral histories, and a timeline that follows a wood cut out of the Cuyahoga River and features African American Canal Captain John Malvin. Another feature of the pop up is a continuum which allows guests to vote with a pebble which Ohio African American individual they would like to learn about. After a large consideration for accessibility and diverse representation of historical lifestyles the names we chose to highlight were George Peake, John Brown, Garret Morgan, and Jean Capers.

Firstly, George Peake was the first African American to settle in Cleveland. Secondly, John Brown was an African American barber, entrepreneur, and assistant to the Underground Railroad who resided in the Cleveland area. Thirdly, Garret Morgan pioneered the invention of the traffic light and “smoke hood”. Lastly, Jean Capers was the first African American woman elected to the Cleveland City Council and served in law until the age of 99. All considered it was troublesome to make a decision about the individuals to be highlighted because the documentation of African Americans in the actual Cuyahoga Valley area is scarce and our group also hoped to connect with individual’s closer to Cleveland by including individuals from Cleveland rather than strictly the Cuyahoga Valley. When our team presented the pop up at a volunteer event we had extremely positive feedback from the historical figures chosen and folks were extremely receptive.

Our highlighted individuals were supplemented by local stories of African Americans in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. For example, an oral history recorded by Ranger Arye tells a story of an African American family that was run out of Northhampton Road in the Valley in the 1930’s. Ranger Arye interviewed a number of individuals who claimed descendence from the family off Northhampton road. Current pictures of the forest alongside Northhampton road show the families’ former house in ruins and secondary sources suggest the family may have been chased out of the Valley due to racial hatred.

Local stories in the pop up, like the family off Northhampton road, were included with the intention to supplement local information to the dialogic questions our group chose. For example, when our pop up was presented we asked volunteers what privilege meant to them in the context of the family off Northhampton road. Information about local African American history in the Cuyahoga Valley is still being actively researched by park historians and the pop-up will be updated as new information presents surfaces. Ultimately, the African American History pop up I created alongside Ranger Hayden and Whitney will be used everywhere throughout the Cuyahoga Valley National Park and will be taken on trips to metropolitan areas to educate about history.

Although the African American pop up was my main project at my internship at the Cuyahoga Valley National Park a typical day at the Cuyahoga Valley National Park looked like the following entry to my internship journal:

“The canopy became thicker as we moved further into the forest that surrounds Kendall Ledges. My smile was wide and the hemlock trees shined emerald green. I leaned forward to the group of kids I was assigned to lead and told them to notice the transformation of the ecosystem around them. As the hemlock trees turned to evergreen a young girl exclaimed “Oh my gosh! It’s dark now!”. With the intention to capitalize on the excitement, I began to tell the group of the Civilian Conservation Corps’ initiatives in the 1930s that aimed to uplift impoverished young men and make parks accessible to everyday Americans. As I began to talk about natural history and the decline of bat populations a group of older hikers joined our group. Correspondingly, I changed the rhetoric of my interpretation to make the information accessible to all ages”.

Bearing my journal entry in mind, a key part of the internship was learning to accommodate individuals with different needs. The National Park Service abides by ACE or Audience Centered Experiences, which hopes to engage guests with visceral hands-on learning instead of inaccessible didactic teaching. During my time at the Cuyahoga Valley National Park, one of the hardest tasks was ACE interpretation for blind community groups. My experiences with the blind groups were on train programs on the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad. I was assigned to describe the significance of the National Park Service in an interactive setting. Usually, when I presented the lesson on the National Park Service I held the National Park Service arrowhead logo and point to different aspects of the design and how each part reflects the values of the National Park Service. For example, the arrowhead itself represents cultural history and the mountain represents geological history and preservation. When I presented the National Park Service lesson to the groups of blind individuals I was faced with the challenge of not having the visual representation I usually relied on. As a consequence, I had to supplement the lack of visual representation with detailed and descriptive language.

I found that language is more accessible than we’d like to think. A big takeaway from my experience with the blind community groups is that we rarely reflect on the filters that we use before we speak. Ultimately, 100% effective communication at all times is not possible but individuals should take the time to reflect on our filters before we speak. Although interpretation was a challenging task at times I now feel comfortable adjusting language and presentation style on a wide variety of contingencies.

Looking back at the entire experience at the park one of the most powerful moments I had was when my supervisor gave me the story of a young woman who I just had a conversation with at a campfire program. I had just got done playing an interactive song for our Whacky for Wetlands campfire program and a young woman came up to me and complimented the performance. After a conversation about music, I steered the woman over to a new pop-up about plastic consumption. We reviewed recycling laws and the increased hazard of worldwide plastic pollution. After a less than cheery read through of plastic facts, we looked at the dialogic question included on the pop up “What is the worth of hope?”. The woman exclaimed that hope was everything that she lived off of through her life. The woman also expressed that her new opportunity to visit the park more often gave her hope. Without pressing for details I agreed that it was noble to live with constant hope.

Later that night after the program our team gathered after the program to share our highlights of the night. After our team disbanded my supervisor approached me and told me that the young woman I talked to that night was a member of a battered women’s shelter. I was awestruck. When I talked to the woman earlier her demeanor was always so calm and collected. Without even realizing I had talked to an individual who had gone through extensive periods of trials and tribulations. After my supervisor told me the woman’s story I reflected on the woman telling me that the park had given her hope and an opportunity to feel alive.

In contrast to my experience growing up in nature that young woman grew up under circumstances that ripped her apart from green spaces and gave her little voice. As I move forward after this internship I will be an advocate for bringing green spaces to all individuals for all the benefits that a National Park can bring to a person’s wellbeing. National Parks give a foundation for clarity of mind and hope. Individuals who have easier access to public parks should take the time to reflect on how public parks can be made accessible to all for collective health as a global community.